Oscar Micheaux was born in the mid-1880s[1. There is some dispute about the year, apparently. Either ’84 or ’85.] in Illinois, grandson to former slaves. He worked in his teens as a Pullman porter in the railroads, then set himself up as a homesteader in or around 1904 in South Dakota.

Oscar Micheaux was born in the mid-1880s[1. There is some dispute about the year, apparently. Either ’84 or ’85.] in Illinois, grandson to former slaves. He worked in his teens as a Pullman porter in the railroads, then set himself up as a homesteader in or around 1904 in South Dakota.

Nine years later, he self-published his first novel, The Conquest, based closely on his own experiences as a black homesteader in an all-white community. Though he first published it anonymously, he sold it door to door himself, and its modest success encouraged Micheaux to write his next two novels, The Forged Note (1915) and The Homesteader (1917).

Apparently during the writing of The Homesteader, Micheaux saw D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, and was simultaneously appalled by its vile portrayal of blacks, and thrilled by its pioneering use of complex, novelistic storytelling in the film medium.

Sometime after the publication of The Homesteader, Micheaux was contacted by the newly-formed Lincoln Motion Picture Company, the first attempt at creating an all-black film studio. They wanted to make Micheaux’s novel into a film, but he wanted more involvement than just providing the source material. Instead of selling the rights, he formed his own production company (financed, in part, by investments from contacts he had made in his Pullman porter days), and made a movie of The Homesteader himself — the first black-produced film in America.

Sometime after the publication of The Homesteader, Micheaux was contacted by the newly-formed Lincoln Motion Picture Company, the first attempt at creating an all-black film studio. They wanted to make Micheaux’s novel into a film, but he wanted more involvement than just providing the source material. Instead of selling the rights, he formed his own production company (financed, in part, by investments from contacts he had made in his Pullman porter days), and made a movie of The Homesteader himself — the first black-produced film in America.

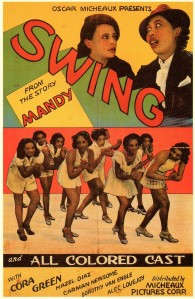

It was a hit, both critically and with black audiences. Micheaux next made two strong answers to Birth of a Nation: Within These Gates (1920) and Symbol of the Unconquered (1920). With that out of the way, he embarked on the most successful career of any black filmmaker in the first half of the twentieth century, maintaining his independence right through his last film in 1947, and becoming one of the few filmmakers to jump successfully to talkies.

He did all of this without help, without any outside guidance, and with a fair amount of competition for a limited market.

He was his own studio, financing, writing, producing, directing, shooting, editing, and even distributing his films himself — literally, he drove each film, one print only, around the midwest and into the northeast in the trunk of his car, to each theater.

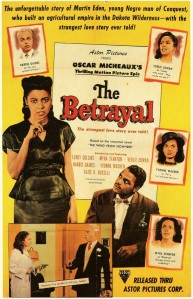

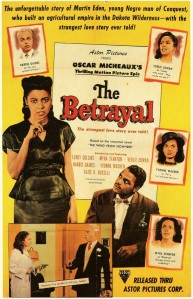

It wasn’t all success. The Depression and World War II eventually made making movies untenable for him, and he returned to novel-writing, putting out four more books in the early and mid-1940s. His final film, The Betrayal, was ambitious, a three-hour epic (based on one of his own books, again) shot with his usual budgetary, technical, and scheduling restraints. Alas, it flopped. Critics hated it, and the first audiences were so negative toward it that Micheaux pulled it from ever showing again. It is now a lost film.

It wasn’t all success. The Depression and World War II eventually made making movies untenable for him, and he returned to novel-writing, putting out four more books in the early and mid-1940s. His final film, The Betrayal, was ambitious, a three-hour epic (based on one of his own books, again) shot with his usual budgetary, technical, and scheduling restraints. Alas, it flopped. Critics hated it, and the first audiences were so negative toward it that Micheaux pulled it from ever showing again. It is now a lost film.

You don’t hear about Oscar Micheaux much. There are a couple of reasons for that.

First, he had the wrong politics. The first half of a twentieth century in black America featured the clash of two separate and opposing ways of viewing race in the country. Booker T. Washington advocated individual self-improvement, “uplifting the race”. W.E.B. Du Bois, to over-simplify quite a bit, advocated reparations and a victim mentality. Du Bois won, eventually, and Micheaux was a strong advocate for Washington, which makes his work uncomfortable, at best, for those who continue to use race and racism as an excuse and a license.

Second, Micheaux was passionate, but he was not an artist. (Or, if he was, his extremely limited budgets defeated his vision pretty thoroughly.) His silent films are quite watchable, but once you get to his talkies, his movies can be rather tough going. You are unlikely to watch any of his sound films and declare that you have just seen a forgotten masterpiece.

However, he remains an important figure in film and American culture, even if he is mostly unknown today.

One reason we can gauge his importance is because copyright law in the first half of the century was not nearly as crazy as it is today.

One reason we can gauge his importance is because copyright law in the first half of the century was not nearly as crazy as it is today.

Stop for a moment, and imagine how things would stand if copyright in Micheaux’s time was exactly what it is now.

Micheaux died in 1951, leaving no heirs as far as I know. His film production companies were all shuttered with the failure of his final film, The Betrayal.

In other words, no person or entity would clearly have inherited his intellectual property (IP). (At that point, in fact, it would appear that nobody would even have wanted it.) But by the terms of present copyright law, his copyright would endure for nearly a hundred years, even without anyone owning it.

Prints of his films went into vaults and storage warehouses, got left in theater projection booths. And if somebody found one, he could legally do nothing with it unless he wanted to risk getting sued or prosecuted. Because an orphaned work that suddenly appears to have value suddenly finds itself claimed by scoundrels and lawyers who have little or no connection to the original creator or owner. (See, for example, Wade Williams’s spurious, legally refuted claims to owning several 1950s films that the courts have found to be in the public domain. It doesn’t stop him from claiming copyright and suing, no matter how many times he’s been smacked down in court.)

Micheaux’s films would all be orphaned works, mouldering unseen because of the dark cloud of legal uncertainty hanging over them. Given the stock they were on, they would decay rapidly, and be lost to humanity, more likely than not.

Luckily for us, copyright law in Micheaux’s time was quite different. Copyright did not attach automatically, and it was not functionally indefinite.

Luckily for us, copyright law in Micheaux’s time was quite different. Copyright did not attach automatically, and it was not functionally indefinite.

Although some of his films have copyright notices on them, only a few were ever actually registered (quite possibly because Micheaux could not afford the price of an extra print to be archived with the registration — recall that his potential market was very small; his budgets were almost all under $10,000, tiny even adjusted for inflation), and those which were registered were never renewed. Under the law at the time, those never registered were public domain immediately, and the rest lapsed into the public domain when they were not renewed.

That means that every one of them is free of legal shenanigans by unscrupulous IP parasites. If you find one of his lost films in your attic, you can restore it, or simply digitize it, and share it with the world, for a price or for free, with no fear of legal consequences.

This freedom means that all of Micheaux’s surviving films are available.

Because of the public domain, his legacy is preserved. It’s that simple.

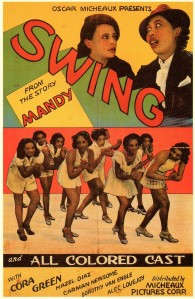

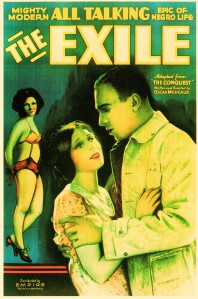

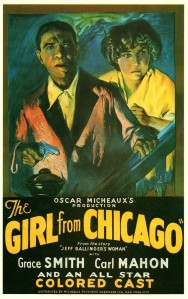

Oscar Micheaux films on the Archive:

On Youtube:

OK, before we get to the album, a few things.

OK, before we get to the album, a few things.